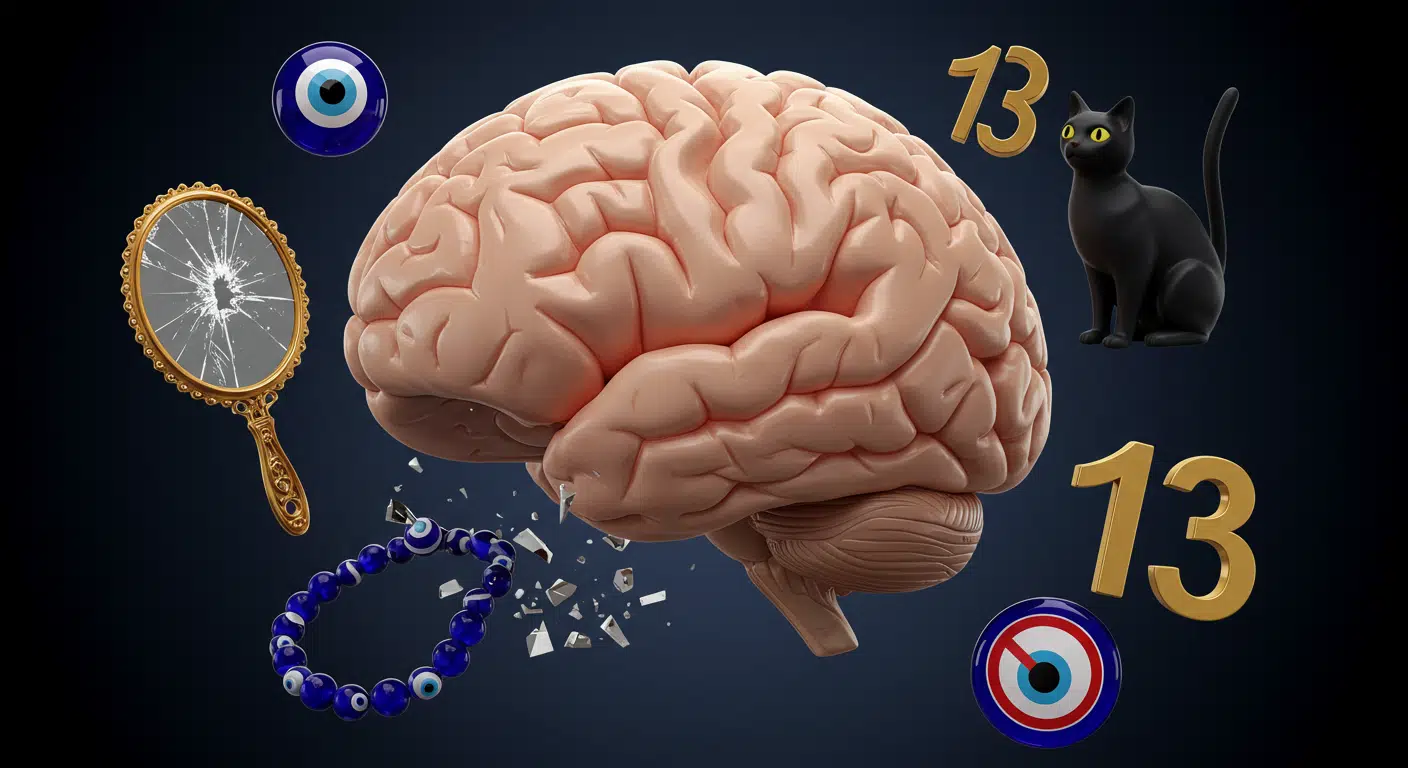

Superstitions are enduring beliefs in supernatural causality that persist across cultures and historical periods despite lacking empirical foundation. They are often dismissed as irrational, yet they serve consistent psychological, social, and emotional functions. The human inclination toward superstitious thinking is deeply rooted in cognitive architecture, developmental patterns, cultural learning, and situational stress responses. These beliefs are not arbitrary; they respond to core human needs for control, meaning, and emotional regulation in uncertain environments.

One of the primary drivers of superstitious belief is the brain’s predisposition to detect patterns in ambiguous or random information. Evolutionarily, the ability to quickly infer agency and causation was adaptive. Early humans who reacted to uncertain environmental cues with caution were more likely to survive, even if those cues were non-threatening. This pattern-detection tendency manifests today in the form of illusory correlations, such as associating bad outcomes with trivial antecedents. Superstitions often arise when individuals attribute causality to coincidental events, such as interpreting a successful outcome as the result of wearing a particular item or engaging in a specific ritual.

Cognitive biases further reinforce these patterns. Confirmation bias leads individuals to remember instances when a superstition appeared to work while disregarding contradictory evidence. A person who wears a “lucky” shirt to an interview and gets the job may ascribe the success to the shirt rather than qualifications or preparation. Illusory correlation involves the perception of a relationship between two variables where none exists—such as assuming that walking under a ladder brings misfortune because of isolated negative experiences following the act.

Superstitions also fulfill emotional and psychological needs by offering comfort in high-stakes or unpredictable contexts. Studies in social psychology demonstrate that people are more likely to engage in superstitious behaviors when faced with uncertainty or stress. Actions such as knocking on wood, avoiding certain numbers, or carrying amulets provide a sense of agency in circumstances where outcomes cannot be controlled. These behaviors function as coping mechanisms, reducing anxiety by creating a structure that mimics causality.

The concept of locus of control—whether individuals perceive outcomes as internally controlled by their actions or externally controlled by fate or chance—also contributes to the prevalence of superstitions. Those with an external locus of control are more likely to rely on rituals or charms to influence events. This is particularly evident in domains such as sports, performance, and gambling, where outcomes are perceived as partially dependent on external variables. Athletes may adhere to elaborate pre-game rituals not because they believe these actions cause success, but because they provide psychological readiness and reduce performance-related stress.

Cultural transmission plays a key role in the persistence of superstitions. These beliefs are passed from generation to generation through language, customs, and rituals. In many cultures, superstitions are embedded in proverbs, rhymes, and idiomatic expressions that enhance memorability and emotional resonance. For example, the phrase “step on a crack, break your mother’s back” embeds a belief in a cause-effect relationship within a rhythmic structure that facilitates early learning. Similarly, metaphors such as “break a leg” in theatrical contexts disguise superstitions as colloquial encouragements.

Language not only preserves superstitions but also encodes broader social values and fears. Gestures such as tucking thumbs in cemeteries (Japan), or the use of evil eye amulets (Mediterranean), reflect communal anxieties about mortality, envy, and spiritual contamination. These practices serve as symbolic rituals that reinforce group identity and shared belief systems. In some societies, superstitions are closely linked with religious or cosmological views and function as extensions of broader moral frameworks.

Developmentally, superstitions may be linked to cognitive traits such as animism and magical thinking, which are common in childhood and often persist into adulthood in attenuated forms. Young children frequently attribute agency to inanimate objects and believe their actions can influence unrelated events. While such thinking usually diminishes with age and education, elements often remain embedded in adult cognition. Adults may unconsciously engage in ontological confusions, attributing mental states or powers to objects or events that do not possess them—believing, for example, that a cursed item brings bad luck or that a specific day is inherently unlucky.

Evolutionary psychology also provides a framework for understanding superstitious behavior as a survival mechanism. Rituals designed to appease unknown forces or deities, common in early human societies, may have promoted group cohesion and reduced feelings of helplessness in unpredictable environments. Even if the rituals themselves had no causal efficacy, they structured behavior and provided shared meaning, which may have enhanced cooperation and collective resilience.

Superstitious behavior also intensifies in response to situational triggers, particularly in environments where outcomes are uncertain and stakes are high. Common domains include sports, exams, performance arts, and medical crises. Gamblers often avoid specific numbers or perform pre-bet rituals to manage perceived risk. Actors follow performance taboos, such as not uttering the name “Macbeth” inside a theater, to protect against bad luck. In these cases, superstition serves as a psychological buffer, converting anxiety into action.

Superstitions adapt to modern contexts. In secular societies, many people no longer believe in the supernatural rationale behind a superstition but still perform the associated ritual out of habit or cultural expectation. Commercialized objects like evil eye charms, feng shui decorations, and numerologically “lucky” products illustrate how superstition blends into consumer culture. In digital spaces, superstitious thinking emerges in practices such as scheduling emails at auspicious times or attributing negative outcomes to symbolic triggers.

Though lacking in logical validity, superstitions provide insight into the universal human experience of uncertainty and vulnerability. They persist not because they are true, but because they function. They regulate emotional responses, promote social bonds, and create frameworks for understanding a complex and often unpredictable world. Recognizing the psychological underpinnings of these beliefs helps demystify them while acknowledging their role in shaping behavior.

Key factors behind superstitious thinking include:

- Cognitive biases such as pattern detection, confirmation bias, and illusory correlation

- Emotional regulation through perceived control and ritualistic behavior

- External locus of control in high-stress or high-uncertainty environments

- Cultural reinforcement via language, tradition, and symbolic rituals

- Developmental carryover from childhood magical thinking and animism

- Evolutionary functions supporting group cohesion and coping mechanisms

- Situational amplification during performance, crisis, or risk scenarios

Superstitions, although irrational, endure as functional responses to psychological and environmental demands. They offer structure, reduce anxiety, and affirm social belonging, revealing not only individual thought patterns but broader cultural systems for navigating the unknown.